Indoor location technology brings Internet-style tracking to physical spaces.

You’ve just tossed a jar of peanut butter in your grocery cart when your smartphone buzzes. You glance down at the screen to see a message that seems downright clairvoyant: Buy some jelly. Get $1 off.

Convenient? Certainly. Creepy? Maybe.

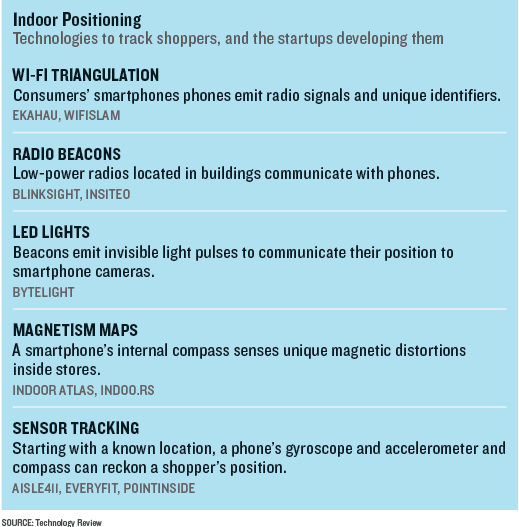

This is one vision for indoor positioning, a fast-evolving technology that is allowing retailers to track shoppers’ physical movements along their aisles in unprecedented detail. In many big-box stores, equipment is already in place to sniff out customers’ smartphones and log data such as how many minutes a person spends in the shoe department.

The technology could eventually give retailers capabilities rivaling those of online stores. On the Web, behavioral ads use records of a person’s browsing history to propose products. Now pharmacies or home improvement stores wanting to sell Kleenex or two-by-fours could soon do the same thing (see “It’s All E-Commerce Now”).

“Not much is known about what shoppers do in stores until they check out at the cashier,” says Todd Sherman, chief marketing officer for Point Inside, a Bellevue, Washington, startup that’s among a score of companies that have raised venture capital funding to perfect indoor tracking and advertising techniques. “This way, you can see what they’re interested in [and] see where they’re going.”

U.S. retailers including Nordstrom, Family Dollar, and American Apparel have experimented with indoor positioning. Some systems use videocameras, sound waves, or even magnetic fields. In September, Apple added a feature called iBeacon to its smartphones; it emits a low-power Bluetooth radio signal, also designed for indoor use.

The most widely used technique is to intercept Wi-Fi signals emitted by shoppers’ smartphones. Triangulating on that signal can estimate the phone’s position to within a few meters. Stores also collect a unique identifier, called a MAC address, for each phone. That allows them to build up behavioral information on return visitors.

Forest City Enterprises triangulates on cellular signals to monitor foot traffic in most of the nearly 20 shopping centers it owns or manages. It says the data helped it decide where to move an escalator that was interfering with an entrance. The company also measures how long visitors stay after a fashion show or concert. Stephanie Shriver-Engdahl, Forest City’s vice president of digital strategy, says the company wants to know, “Do they get one soda, hop in the car, and leave? Or are they staying longer?” In the future, foot-traffic data could be used to set lease prices, she says.

Because indoor tracking is still complex, it may not take off the way some proponents expect. “Simply because the technology exists and it’s possible doesn’t mean that marketers will do it,” says Greg Sterling, an analyst with Opus Research. “Some of this stuff may never happen.”

But Don Dodge, a Google executive who has invested in several indoor location companies, believes the technology “will be bigger than GPS” or online maps. That’s because people spend most of their time indoors, he says, where GPS signals are often too weak to be useful.

Google has already expanded its maps to include diagrams of the inside of museums, airports, and large stores in 17 countries, like Hong Kong’s Tai Po Mega Mall. The company is betting maps will continue to gain importance for people on foot once it begins selling its head-mounted computer, Glass. “Indoor location is going to be huge,” Dodge says. “It’s going to be the biggest thing to hit retailing and couponing that we’ve ever seen.”

Before that happens, retailers may have to brave a privacy debate. Nordstrom suffered a public-relations black eye this year after it began tracking customers in 17 stores using a Wi-Fi system developed by Euclid Analytics. Some customers who read signs at store entrances explaining the technology complained about an invasion of their privacy.

Nordstrom says it ended the test a few months ago. “Basically, it had run its course, we learned some things, and we moved on,” says Colin Johnson, a Nordstrom spokesman. “At the same time, we recognize that we have to continue to test and try new things in order to evolve and stay relevant to the customer.”

Since the Nordstrom episode, retailers have become reluctant to acknowledge their use of indoor tracking. But RetailNext, a company offering “comprehensive in-store analytics,” says its products are being used by 100 large retailers and in thousands of stores. Euclid also says it has 100 customers, including Home Depot.

Source: MIT